based on this map what was true of the two city states that came to dominate ancient greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the fifth and quaternary centuries BC) in Ancient Greece,[1] marked by much of the eastern Aegean and northern regions of Greek culture (such as Ionia and Republic of macedonia) gaining increased autonomy from the Western farsi Empire; the acme flourishing of autonomous Athens; the Beginning and Second Peloponnesian Wars; the Spartan and and then Theban hegemonies; and the expansion of Macedonia under Philip 2. Much of the early defining politics, creative idea (architecture, sculpture), scientific thought, theatre, literature and philosophy of Western civilization derives from this flow of Greek history, which had a powerful influence on the later Roman Empire. The Classical era ended after Philip II'south unification of about of the Greek earth against the common enemy of the Persian Empire, which was conquered inside xiii years during the wars of Alexander the Smashing, Philip's son.

In the context of the art, compages, and civilisation of Ancient Greece, the Classical menstruation corresponds to most of the fifth and 4th centuries BC (the about common dates being the fall of the terminal Athenian tyrant in 510 BC to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC). The Classical period in this sense follows the Greek Dark Ages and Primitive menstruation and is in turn succeeded by the Hellenistic period.

fifth century BC [edit]

Construction of the Parthenon began in the 5th century BC

This century is essentially studied from the Athenian outlook because Athens has left united states more narratives, plays, and other written works than any of the other ancient Greek states. From the perspective of Athenian civilization in Classical Greece, the period generally referred to as the 5th century BC extends slightly into the 6th century BC. In this context, one might consider that the first pregnant event of this century occurs in 508 BC, with the fall of the final Athenian tyrant and Cleisthenes' reforms. Withal, a broader view of the whole Greek earth might place its beginning at the Ionian Revolt of 500 BC, the consequence that provoked the Farsi invasion of 492 BC. The Persians were defeated in 490 BC. A second Persian attempt, in 481–479 BC, failed as well, despite having overrun much of mod-day Greece (due north of the Isthmus of Corinth) at a crucial signal during the war following the Boxing of Thermopylae and the Battle of Artemisium.[two] [3] The Delian League then formed, under Athenian hegemony and as Athens' musical instrument. Athens' successes caused several revolts among the allied cities, all of which were put downwards by strength, but Athenian dynamism finally awoke Sparta and brought about the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC. Subsequently both forces were spent, a brief peace came about; then the war resumed to Sparta'south advantage. Athens was definitively defeated in 404 BC, and internal Athenian agitations mark the cease of the 5th century BC in Hellenic republic.

Since its offset, Sparta had been ruled by a diarchy. This meant that Sparta had 2 kings ruling concurrently throughout its entire history. The two kingships were both hereditary, vested in the Agiad dynasty and the Eurypontid dynasty. According to legend, the respective hereditary lines of these two dynasties sprang from Eurysthenes and Procles, twin descendants of Hercules. They were said to accept conquered Sparta two generations afterward the Trojan War.

Athens under Cleisthenes [edit]

In 510 BC, Spartan troops helped the Athenians overthrow their king, the tyrant Hippias, son of Peisistratos. Cleomenes I, king of Sparta, put in place a pro-Spartan oligarchy headed by Isagoras. But his rival Cleisthenes, with the support of the middle form and aided by pro-democracy citizens, took over. Cleomenes intervened in 508 and 506 BC, but could not stop Cleisthenes, at present supported by the Athenians. Through Cleisthenes' reforms, the people endowed their city with isonomic institutions—equal rights for all citizens (though only men were citizens)—and established ostracism.

The isonomic and isegoric (equal freedom of spoken communication)[4] democracy was first organized into about 130 demes, which became the bones borough element. The 10,000 citizens exercised their power as members of the assembly (ἐκκλησία, ekklesia), headed past a council of 500 citizens chosen at random.

The city's administrative geography was reworked, in society to create mixed political groups: not federated past local interests linked to the sea, to the city, or to farming, whose decisions (eastward.m. a declaration of war) would depend on their geographical position. The territory of the city was as well divided into 30 trittyes equally follows:

- ten trittyes in the coastal region (παρᾰλία, paralia)

- ten trittyes in the ἄστυ (astu), the urban centre

- ten trittyes in the rural interior, (μεσογεία, mesogia).

A tribe consisted of three trittyes, selected at random, one from each of the 3 groups. Each tribe therefore always acted in the interest of all iii sectors.

It was this corpus of reforms that allowed the emergence of a wider republic in the 460s and 450s BC.

The Western farsi wars [edit]

In Ionia (the modernistic Aegean coast of Turkey), the Greek cities, which included great centres such equally Miletus and Halicarnassus, were unable to maintain their independence and came nether the rule of the Persian Empire in the mid-6th century BC. In 499 BC that region's Greeks rose in the Ionian Defection, and Athens and some other Greek cities sent aid, only were apace forced to back downwards after defeat in 494 BC at the Battle of Lade. Asia Modest returned to Farsi control.

In 492 BC, the Persian general Mardonius led a campaign through Thrace and Macedonia. He was victorious and again subjugated the former and conquered the latter,[v] simply he was wounded and forced to retreat back into Asia Modest. In addition, a armada of around ane,200 ships that accompanied Mardonius on the expedition was wrecked by a tempest off the coast of Mount Athos. Later, the generals Artaphernes and Datis led a successful naval expedition against the Aegean islands.

In 490 BC, Darius the Great, having suppressed the Ionian cities, sent a Persian fleet to punish the Greeks. (Historians are uncertain about their number of men; accounts vary from 18,000 to 100,000.) They landed in Attica intending to have Athens, but were defeated at the Battle of Marathon past a Greek army of 9,000 Athenian hoplites and ane,000 Plataeans led by the Athenian general Miltiades. The Persian fleet continued to Athens only, seeing information technology garrisoned, decided non to attempt an assault.

In 480 BC, Darius' successor Xerxes I sent a much more powerful force of 300,000 by land, with 1,207 ships in support, across a double pontoon bridge over the Hellespont. This army took Thrace, before descending on Thessaly and Boeotia, whilst the Farsi navy skirted the coast and resupplied the ground troops. The Greek fleet, meanwhile, dashed to block Cape Artemision. Subsequently being delayed by Leonidas I, the Spartan male monarch of the Agiad Dynasty, at the Battle of Thermopylae (a boxing fabricated famous by the 300 Spartans who faced the entire Persian army), Xerxes advanced into Attica, and captured and burned Athens. The subsequent Battle of Artemisium resulted in the capture of Euboea, bringing most of mainland Greece north of the Isthmus of Corinth nether Persian control.[two] [iii] However, the Athenians had evacuated the city of Athens past body of water before Thermopylae, and under the control of Themistocles, they defeated the Western farsi fleet at the Battle of Salamis.

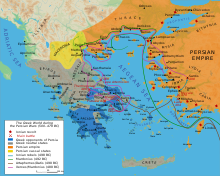

Map of the start phases of the Greco-Western farsi Wars (500–479 BC)

In 483 BC, during the catamenia of peace between the two Persian invasions, a vein of argent ore had been discovered in the Laurion (a minor mountain range well-nigh Athens), and the hundreds of talents mined at that place were used to build 200 warships to combat Aeginetan piracy. A year later, the Greeks, under the Spartan Pausanias, defeated the Persian ground forces at Plataea. The Persians then began to withdraw from Hellenic republic, and never attempted an invasion once again.

The Athenian fleet then turned to chasing the Persians from the Aegean Ocean, defeating their fleet decisively in the Battle of Mycale; and then in 478 BC the armada captured Byzantium. At that time Athens enrolled all the island states and some mainland ones into an alliance chosen the Delian League, so named considering its treasury was kept on the sacred island of Delos. The Spartans, although they had taken role in the war, withdrew into isolation afterwards, allowing Athens to establish unchallenged naval and commercial ability.

The Peloponnesian war [edit]

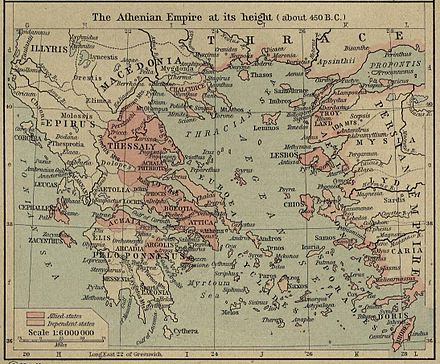

Cities at the offset of the Peloponnesian State of war

Origins of the Delian League and the Peloponnesian League [edit]

In 431 BC war broke out betwixt Athens and Sparta. The war was a struggle not merely between two city-states simply rather between 2 coalitions, or leagues of city-states:[6] the Delian League, led past Athens, and the Peloponnesian League, led by Sparta.

Delian league [edit]

The Delian League grew out of the need to present a unified front of all Greek metropolis-states against Persian aggression. In 481 BC, Greek city-states, including Sparta, met in the first of a series of "congresses" that strove to unify all the Greek urban center-states against the danger of another Persian invasion.[vii] The coalition that emerged from the first congress was named the "Hellenic League" and included Sparta. Persia, under Xerxes, invaded Greece in September 481 BC, but the Athenian navy defeated the Persian navy. The Persian land forces were delayed in 480 BC by a much smaller force of 300 Spartans, 400 Thebans and 700 men from Boeotian Thespiae at the Battle of Thermopylae.[viii] The Persians left Greece in 479 BC after their defeat at Plataea.[9]

Plataea was the concluding battle of Xerxes' invasion of Greece. Later on this, the Persians never over again tried to invade Greece. With the disappearance of this external threat, cracks appeared in the united front of the Hellenic League.[ten] In 477, Athens became the recognised leader of a coalition of city-states that did not include Sparta. This coalition met and formalized their relationship at the holy city of Delos.[eleven] Thus, the League took the name "Delian League". Its formal purpose was to liberate Greek cities still nether Persian control.[12] However, it became increasingly credible that the Delian League was really a front for Athenian hegemony throughout the Aegean.[13]

Peloponnesian (or Spartan) league [edit]

A competing coalition of Greek city-states centred around Sparta arose, and became more important equally the external Persian threat subsided. This coalition is known as the Peloponnesian League. However, dissimilar the Hellenic League and the Delian League, this league was not a response to any external threat, Persian or otherwise: it was unabashedly an instrument of Spartan policy aimed at Sparta's security and Spartan authorisation over the Peloponnese peninsula.[fourteen] The term "Peloponnesian League" is a misnomer. Information technology was not really a "league" at all. Nor was it really "Peloponnesian".[14] At that place was no equality at all between the members, every bit might exist implied past the term "league". Furthermore, most of its members were located outside the Peloponnese Peninsula.[14] The terms "Spartan League" and "Peloponnesian League" are modern terms. Contemporaries instead referred to "Lacedaemonians and their Allies" to describe the "league".[14]

The league had its origins in Sparta'due south conflict with Argos, another metropolis on the Peloponnese Peninsula. In the 7th century BC, Argos dominated the peninsula. Fifty-fifty in the early on 6th century, the Argives attempted to command the northeastern part of the peninsula. The rise of Sparta in the 6th century brought Sparta into conflict with Argos. However, with the conquest of the Peloponnesian city-country of Tegea in 550 BC and the defeat of the Argives in 546 BC, the Spartans' control began to reach well beyond the borders of Laconia.

The thirty years peace [edit]

Every bit the two coalitions grew, their dissever interests kept coming into conflict. Nether the influence of King Archidamus II (the Eurypontid king of Sparta from 476 BC through 427 BC), Sparta, in the late summer or early autumn of 446 BC, ended the Xxx Years Peace with Athens. This treaty took result the next winter in 445 BC[fifteen] Under the terms of this treaty, Greece was formally divided into two large power zones.[16] Sparta and Athens agreed to stay within their own power zone and not to interfere in the other'due south. Despite the Thirty Years Peace, information technology was clear that war was inevitable.[17] Equally noted above, at all times during its history down to 221 BC, Sparta was a "diarchy" with two kings ruling the city-state concurrently. One line of hereditary kings was from the Eurypontid Dynasty while the other king was from the Agiad Dynasty. With the signing of the 30 Years Peace treaty, Archidamus Ii felt he had successfully prevented Sparta from inbound into a war with its neighbours.[18] Even so, the strong state of war party in Sparta soon won out and in 431 BC Archidamus was forced to get to war with the Delian League. Nevertheless, in 427 BC, Archidamus II died and his son, Agis 2 succeeded to the Eurypontid throne of Sparta.[xix]

Causes of the Peloponnesian war [edit]

The immediate causes of the Peloponnesian War vary from business relationship to business relationship. Withal three causes are fairly consistent among the aboriginal historians, namely Thucydides and Plutarch. Prior to the war, Corinth and ane of its colonies, Corcyra (modern-day Corfu), went to state of war in 435 BC over the new Corcyran colony of Epidamnus.[20] Sparta refused to become involved in the disharmonize and urged an arbitrated settlement of the struggle.[21] In 433 BC, Corcyra sought Athenian assistance in the state of war. Corinth was known to be a traditional enemy of Athens. Nevertheless, to further encourage Athens to enter the conflict, Corcyra pointed out how useful a friendly relationship with Corcyra would be, given the strategic locations of Corcyra itself and the colony of Epidamnus on the eastward shore of the Adriatic Sea.[22] Furthermore, Corcyra promised that Athens would accept the utilise of Corcyra's navy, the tertiary-largest in Greece. This was too good of an offering for Athens to turn down. Accordingly, Athens signed a defensive alliance with Corcyra.

The next yr, in 432 BC, Corinth and Athens argued over command of Potidaea (near modern-day Nea Potidaia), eventually leading to an Athenian siege of Potidaea.[23] In 434–433 BC Athens issued the "Megarian Decrees", a series of decrees that placed economic sanctions on the Megarian people.[24] The Peloponnesian League accused Athens of violating the 30 Years Peace through all of the aforementioned actions, and, accordingly, Sparta formally declared state of war on Athens.

Many historians consider these to be only the immediate causes of the war. They would argue that the underlying cause was the growing resentment on the part of Sparta and its allies at the dominance of Athens over Greek affairs. The war lasted 27 years, partly because Athens (a naval power) and Sparta (a state-based military power) found it difficult to come up to grips with each other.

The Peloponnesian war: Opening stages (431–421 BC) [edit]

Sparta's initial strategy was to invade Attica, but the Athenians were able to retreat behind their walls. An outbreak of plague in the metropolis during the siege acquired many deaths, including that of Pericles. At the aforementioned time the Athenian fleet landed troops in the Peloponnesus, winning battles at Naupactus (429) and Pylos (425). However, these tactics could bring neither side a decisive victory. After several years of inconclusive campaigning, the moderate Athenian leader Nicias concluded the Peace of Nicias (421).

The Peloponnesian war: 2d phase (418–404 BC) [edit]

In 418 BC, notwithstanding, conflict between Sparta and the Athenian ally Argos led to a resumption of hostilities. Alcibiades was one of the virtually influential voices in persuading the Athenians to ally with Argos against the Spartans.[25] At the Mantinea Sparta defeated the combined armies of Athens and her allies. Appropriately, Argos and the residuum of the Peloponnesus was brought back under the control of Sparta.[25] The return of peace allowed Athens to exist diverted from meddling in the diplomacy of the Peloponnesus and to concentrate on building up the empire and putting their finances in lodge. Soon trade recovered and tribute began, in one case once again, rolling into Athens.[25] A strong "peace party" arose, which promoted avoidance of war and continued concentration on the economic growth of the Athenian Empire. Concentration on the Athenian Empire, even so, brought Athens into conflict with some other Greek state.

The Melian expedition (416 BC) [edit]

Ever since the germination of the Delian League in 477 BC, the isle of Melos had refused to join. By refusing to join the League, still, Melos reaped the benefits of the League without bearing any of the burdens.[26] In 425 BC, an Athenian army under Cleon attacked Melos to strength the island to join the Delian League. Even so, Melos fought off the assault and was able to maintain its neutrality.[26] Farther conflict was inevitable and in the spring of 416 BC the mood of the people in Athens was inclined toward military adventure. The isle of Melos provided an outlet for this energy and frustration for the armed services political party. Furthermore, at that place appeared to be no real opposition to this armed forces trek from the peace political party. Enforcement of the economic obligations of the Delian League upon rebellious city-states and islands was a ways by which continuing trade and prosperity of Athens could be assured. Melos alone amongst all the Cycladic Islands located in the south-west Aegean Sea had resisted joining the Delian League.[26] This continued rebellion provided a bad example to the residue of the members of the Delian League.

The contend between Athens and Melos over the effect of joining the Delian League is presented by Thucydides in his Melian Dialogue.[27] The argue did not in the end resolve any of the differences betwixt Melos and Athens and Melos was invaded in 416 BC, and soon occupied by Athens. This success on the part of Athens whetted the appetite of the people of Athens for further expansion of the Athenian Empire.[28] Accordingly, the people of Athens were set up for war machine activity and tended to support the military political party, led by Alcibiades.

The Sicilian expedition (415–413 BC) [edit]

Thus, in 415 BC, Alcibiades constitute support within the Athenian Associates for his position when he urged that Athens launch a major expedition against Syracuse, a Peloponnesian marry in Sicily.[29] Segesta, a town in Sicily, had requested Athenian assistance in their war with some other Sicilian town—the town of Selinus. Although Nicias was a sceptic about the Sicilian Expedition, he was appointed along with Alcibiades to lead the expedition.[30]

Withal, unlike the trek against Melos, the citizens of Athens were securely divided over Alcibiades' proposal for an expedition to furthermost Sicily. In June 415 BC, on the very eve of the departure of the Athenian armada for Sicily, a ring of vandals in Athens defaced the many statues of the god Hermes that were scattered throughout the city of Athens.[31] This action was blamed on Alcibiades and was seen equally a bad omen for the coming campaign.[32] In all likelihood, the coordinated action against the statues of Hermes was the action of the peace political party.[33] Having lost the debate on the consequence, the peace party was desperate to weaken Alcibiades' hold on the people of Athens. Successfully blaming Alcibiades for the action of the vandals would have weakened Alcibiades and the war party in Athens. Furthermore, information technology is unlikely that Alcibiades would take deliberately defaced the statues of Hermes on the very eve of his departure with the fleet. Such defacement could but take been interpreted every bit a bad omen for the trek that he had long advocated.

Fifty-fifty before the armada reached Sicily, word arrived to the fleet that Alcibiades was to be arrested and charged with sacrilege of the statues of Hermes, prompting Alcibiades to flee to Sparta.[34] When the armada after landed in Sicily and the battle was joined, the expedition was a complete disaster. The entire expeditionary force was lost and Nicias was captured and executed. This was one of the nearly burdensome defeats in the history of Athens.

Alcibiades in Sparta [edit]

Meanwhile, Alcibiades betrayed Athens and became a primary counselor to the Spartans and began to counsel them on the best way to defeat his native state. Alcibiades persuaded the Spartans to begin building a real navy for the offset time—large enough to challenge the Athenian superiority at bounding main. Additionally, Alcibiades persuaded the Spartans to ally themselves with their traditional foes—the Persians. Equally noted below, Alcibiades before long establish himself in controversy in Sparta when he was accused of having seduced Timaea, the wife of Agis Two, the Eurypontid rex of Sparta.[xix] Accordingly, Alcibiades was required to flee from Sparta and seek the protection of the Farsi Court.

Persia intervenes [edit]

In the Western farsi courtroom, Alcibiades now betrayed both Athens and Sparta. He encouraged Persia to give Sparta financial aid to build a navy, advising that long and continuous warfare between Sparta and Athens would weaken both city-states and permit the Persians to boss the Greek peninsula.

Amongst the war political party in Athens, a conventionalities arose that the catastrophic defeat of the military expedition to Sicily in 415–413 could have been avoided if Alcibiades had been immune to lead the expedition. Thus, despite his treacherous flight to Sparta and his collaboration with Sparta and later with the Persian court, at that place arose a need amid the war political party that Alcibiades be allowed to return to Athens without existence arrested. Alcibiades negotiated with his supporters on the Athenian-controlled island of Samos. Alcibiades felt that "radical democracy" was his worst enemy. Appropriately, he asked his supporters to initiate a coup to establish an oligarchy in Athens. If the insurrection were successful Alcibiades promised to return to Athens. In 411, a successful oligarchic coup was mounted in Athens, past a grouping which became known as "the 400". Notwithstanding, a parallel endeavor by the 400 to overthrow commonwealth in Samos failed. Alcibiades was immediately made an admiral (navarch) in the Athenian navy. Subsequently, due to democratic pressures, the 400 were replaced by a broader oligarchy called "the 5000". Alcibiades did not immediately return to Athens. In early on 410, Alcibiades led an Athenian fleet of 18 triremes against the Persian-financed Spartan fleet at Abydos nigh the Hellespont. The Battle of Abydos had really begun earlier the arrival of Alcibiades, and had been inclining slightly toward the Athenians. Notwithstanding, with the inflow of Alcibiades, the Athenian victory over the Spartans became a rout. Only the approach of nightfall and the movement of Persian troops to the coast where the Spartans had beached their ships saved the Spartan navy from total destruction.

Post-obit Alcibiades' advice, the Persian Empire had been playing Sparta and Athens off against each other. However, as weak equally the Spartan navy was subsequently the Battle of Abydos, the Persian navy direct assisted the Spartans. Alcibiades then pursued and met the combined Spartan and Persian fleets at the Battle of Cyzicus later in the spring of 410, achieving a significant victory.

Lysander and the end of the state of war [edit]

With the financial help of the Persians, Sparta built a fleet to challenge Athenian naval supremacy. With the new armada and new military leader Lysander, Sparta attacked Abydos, seizing the strategic initiative. Past occupying the Hellespont, the source of Athens' grain imports, Sparta effectively threatened Athens with starvation. [35] In response, Athens sent its last remaining fleet to confront Lysander, but were decisively defeated at Aegospotami (405 BC). The loss of her fleet threatened Athens with bankruptcy. In 404 BC Athens sued for peace, and Sparta dictated a predictably stern settlement: Athens lost her city walls, her fleet, and all of her overseas possessions. Lysander abolished the democracy and appointed in its place an oligarchy called the "Thirty Tyrants" to govern Athens.

Meanwhile, in Sparta, Timaea gave nativity to a child. The child was given the proper name Leotychidas, after the dandy grandfather of Agis Ii—King Leotychidas of Sparta. However, because of Timaea's alleged thing with Alcibiades, information technology was widely rumoured that the young Leotychidas was fathered by Alcibiades.[19] Indeed, Agis Ii refused to acknowledge Leotychidas equally his son until he relented, in front end of witnesses, on his deathbed in 400 BC.[36]

Upon the death of Agis Two, Leotychidas attempted to claim the Eurypontid throne for himself, merely this was met with an outcry, led by Lysander, who was at the height of his influence in Sparta.[36] Lysander argued that Leotychidas was a bastard and could non inherit the Eurypontid throne;[36] instead he backed the hereditary claim of Agesilaus, son of Agis by another married woman. With Lysander's support, Agesilaus became the Eurypontid male monarch as Agesilaus 2, expelled Leotychidas from the land, and took over all of Agis' estates and property.

fourth century BC [edit]

- Related articles: Spartan hegemony and Theban hegemony

The end of the Peloponnesian State of war left Sparta the master of Greece, only the narrow outlook of the Spartan warrior elite did not suit them to this role.[37] Within a few years the autonomous political party regained power in Athens and in other cities. In 395 BC the Spartan rulers removed Lysander from role, and Sparta lost her naval supremacy. Athens, Argos, Thebes, and Corinth, the latter ii old Spartan allies, challenged Sparta's say-so in the Corinthian State of war, which ended inconclusively in 387 BC. That aforementioned year Sparta shocked the Greeks past concluding the Treaty of Antalcidas with Persia. The agreement turned over the Greek cities of Ionia and Republic of cyprus, reversing a hundred years of Greek victories against Persia. Sparta then tried to farther weaken the power of Thebes, which led to a state of war in which Thebes allied with its old enemy Athens.

Then the Theban generals Epaminondas and Pelopidas won a decisive victory at Leuctra (371 BC). The consequence of this battle was the stop of Spartan supremacy and the institution of Theban authority, but Athens herself recovered much of her former power considering the supremacy of Thebes was short-lived. With the death of Epaminondas at Mantinea (362 BC) the city lost its greatest leader and his successors blundered into an ineffectual x-year state of war with Phocis. In 346 BC the Thebans appealed to Philip Ii of Macedon to help them against the Phocians, thus drawing Macedon into Greek diplomacy for the first time.[38]

The Peloponnesian War was a radical turning point for the Greek world. Before 403 BC, the state of affairs was more defined, with Athens and its allies (a zone of domination and stability, with a number of island cities benefiting from Athens' maritime protection), and other states outside this Athenian Empire. The sources denounce this Athenian supremacy (or hegemony) every bit smothering and disadvantageous.[note 1]

After 403 BC, things became more complicated, with a number of cities trying to create similar empires over others, all of which proved short-lived. The kickoff of these turnarounds was managed past Athens equally early on equally 390 BC, allowing it to re-establish itself equally a major ability without regaining its sometime glory.

The autumn of Sparta [edit]

This empire was powerful but short-lived. In 405 BC, the Spartans were masters of all—of Athens' allies and of Athens itself—and their power was undivided. By the cease of the century, they could not even defend their own metropolis. Every bit noted above, in 400 BC, Agesilaus became king of Sparta.[39]

Foundation of a Spartan empire [edit]

The subject of how to reorganize the Athenian Empire as role of the Spartan Empire provoked much heated fence among Sparta's full citizens. The admiral Lysander felt that the Spartans should rebuild the Athenian empire in such a way that Sparta profited from it. Lysander tended to be too proud to take advice from others.[40] Prior to this, Spartan law forbade the use of all precious metals by individual citizens, with transactions being carried out with cumbersome iron ingots (which more often than not discouraged their accumulation) and all precious metals obtained by the city becoming state holding. Without the Spartans' support, Lysander's innovations came into effect and brought a neat deal of profit for him—on Samos, for example, festivals known as Lysandreia were organized in his honour. He was recalled to Sparta, and in one case in that location did not attend to any important matters.

Sparta refused to see Lysander or his successors dominate. Not wanting to found a hegemony, they decided later on 403 BC not to support the directives that he had fabricated.

Agesilaus came to power by accident at the start of the 4th century BC. This accidental accretion meant that, unlike the other Spartan kings, he had the advantage of a Spartan instruction. The Spartans at this date discovered a conspiracy against the laws of the city conducted by Cinadon and as a result concluded in that location were also many dangerous worldly elements at work in the Spartan state.

Agesilaus employed a political dynamic that played on a feeling of pan-Hellenic sentiment and launched a successful campaign against the Persian empire.[41] Again, the Farsi empire played both sides against each other. The Persian Court supported Sparta in the rebuilding of their navy while simultaneously funding the Athenians, who used Persian subsidies to rebuild their long walls (destroyed in 404 BC) as well as to reconstruct their fleet and win a number of victories.

For most of the get-go years of his reign, Agesilaus had been engaged in a state of war against Persia in the Aegean Ocean and in Asia Minor.[42] In 394 BC, the Spartan authorities ordered Agesilaus to render to mainland Greece. While Agesilaus had a large office of the Spartan Regular army in Asia Modest, the Spartan forces protecting the homeland had been attacked by a coalition of forces led past Corinth.[43] At the Boxing of Haliartus the Spartans had been defeated by the Theban forces. Worse yet, Lysander, Sparta'due south chief military machine leader, had been killed during the battle.[44] This was the start of what became known as the "Corinthian War" (395–387 BC).[41] Upon hearing of the Spartan loss at Haliartus and of the expiry of Lysander, Agesilaus headed out of Asia Minor, dorsum beyond the Hellespont, beyond Thrace and back towards Greece. At the Battle of Coronea, Agesilaus and his Spartan Regular army defeated a Theban forcefulness. During the war, Corinth drew support from a coalition of traditional Spartan enemies—Argos, Athens and Thebes.[45] Notwithstanding, when the war descended into guerilla tactics, Sparta decided that information technology could non fight on ii fronts and then chose to ally with Persia.[45] The long Corinthian War finally ended with the Peace of Antalcidas or the King's Peace, in which the "Bully Male monarch" of Persia, Artaxerxes Ii, pronounced a "treaty" of peace between the various city-states of Hellenic republic which broke up all "leagues" of city-states on Greek mainland and in the islands of the Aegean Sea. Although this was looked upon as "independence" for some city-states, the effect of the unilateral "treaty" was highly favourable to the interests of the Persian Empire.

The Corinthian War revealed a significant dynamic that was occurring in Greece. While Athens and Sparta fought each other to exhaustion, Thebes was rise to a position of say-so among the various Greek city-states.

The peace of Antalcidas [edit]

In 387 BC, an edict was promulgated past the Persian king, preserving the Greek cities of Asia Modest and Cyprus as well as the independence of the Greek Aegean cities, except for Lymnos, Imbros and Skyros, which were given over to Athens.[46] It dissolved existing alliances and federations and forbade the formation of new ones. This is an ultimatum that benefited Athens merely to the extent that Athens held onto three islands. While the "Great King," Artaxerxes, was the guarantor of the peace, Sparta was to human action every bit Persia's agent in enforcing the Peace.[47] To the Persians this document is known as the "King'due south Peace." To the Greeks, this document is known as the Peace of Antalcidas, later on the Spartan diplomat Antalcidas who was sent to Persia equally negotiator. Sparta had been worried most the developing closer ties between Athens and Persia. Accordingly, Antalcidas was directed to get whatever agreement he could from the "Great King". Accordingly, the "Peace of Antalcidas" is non a negotiated peace at all. Rather it is a surrender to the interests of Persia, drafted entirely for its benefit.[47]

Spartan interventionism [edit]

On the other mitt, this peace had unexpected consequences. In accordance with information technology, the Boeotian League, or Boeotian confederacy, was dissolved in 386 BC.[48] This confederacy was dominated by Thebes, a city hostile to the Spartan hegemony. Sparta carried out large-calibration operations and peripheral interventions in Epirus and in the northward of Greece, resulting in the capture of the fortress of Thebes, the Cadmea, later on an expedition in the Chalcidice and the capture of Olynthos. It was a Theban political leader who suggested to the Spartan full general Phoibidas that Sparta should seize Thebes itself. This human activity was sharply condemned, though Sparta eagerly ratified this unilateral move by Phoibidas. The Spartan set on was successful and Thebes was placed under Spartan control.[49]

Clash with Thebes [edit]

In 378 BC, the reaction to Spartan control over Thebes was broken past a popular uprising within Thebes. Elsewhere in Greece, the reaction confronting Spartan hegemony began when Sphodrias, another Spartan full general, tried to conduct out a surprise attack on Piraeus.[50] Although the gates of Piraeus were no longer fortified, Sphodrias was driven off before Piraeus. Dorsum in Sparta, Sphodrias was put on trial for the failed attack, just was acquitted by the Spartan court. However, the attempted assault triggered an alliance between Athens and Thebes.[fifty] Sparta would now have to fight them both together. Athens was trying to recover from its defeat in the Peloponnesian State of war at the easily of Sparta'due south "navarch" Lysander in the disaster of 404 BC. The rising spirit of rebellion confronting Sparta also fueled Thebes' try to restore the former Boeotian confederacy.[51] In Boeotia, the Theban leaders Pelopidas and Epaminondas reorganized the Theban army and began to free the towns of Boeotia from their Spartan garrisons, one by one, and incorporated these towns into the revived Boeotian League.[47] Pelopidas won a peachy victory for Thebes over a much larger Spartan force in the Battle of Tegyra in 375 BC.[52]

Theban authorization grew so spectacularly in such a brusk time that Athens came to mistrust the growing Theban power. Athens began to consolidate its position again through the formation of a second Athenian League.[53] Attending was fatigued to growing power of Thebes when information technology began interfering in the political affairs of its neighbor, Phocis, and, particularly, later Thebes razed the city of Plataea, a long-standing marry of Athens, in 375 BC.[54] The destruction of Plataea caused Athens to negotiate an alliance with Sparta against Thebes, in that same year.[54] In 371, the Theban regular army, led by Epaminondas, inflicted a bloody defeat on Spartan forces at Boxing of Leuctra. Sparta lost a big office of its army and 400 of its 2,000 denizen-troops. The Battle of Leuctra was a watershed in Greek history.[54] Epaminondas' victory ended a long history of Spartan armed services prestige and dominance over Hellenic republic and the catamenia of Spartan hegemony was over. However, Spartan hegemony was not replaced past Theban, but rather by Athenian hegemony.

The rising of Athens [edit]

Financing the league [edit]

It was of import to erase the bad memories of the former league. Its fiscal system was non adopted, with no tribute being paid. Instead, syntaxeis were used, irregular contributions as and when Athens and its allies needed troops, collected for a precise reason and spent every bit quickly as possible. These contributions were not taken to Athens—unlike the 5th century BC organization, there was no central exchequer for the league—but to the Athenian generals themselves.

The Athenians had to make their own contribution to the alliance, the eisphora. They reformed how this revenue enhancement was paid, creating a system in advance, the Proseiphora, in which the richest individuals had to pay the whole sum of the tax and so be reimbursed by other contributors. This system was apace assimilated into a liturgy.

Athenian hegemony halted [edit]

This league responded to a existent and present need. On the footing, still, the situation within the league proved to have inverse little from that of the fifth century BC, with Athenian generals doing what they wanted and able to extort funds from the league. Alliance with Athens again looked unattractive and the allies complained.

The main reasons for the eventual failure were structural. This brotherhood was only valued out of fear of Sparta, which evaporated after Sparta's fall in 371 BC, losing the alliance its sole 'raison d'etre'. The Athenians no longer had the means to fulfill their ambitions, and found it difficult merely to finance their own navy, permit solitary that of an entire alliance, and then could not properly defend their allies. Thus, the tyrant of Pherae was able to destroy a number of cities with dispensation. From 360 BC, Athens lost its reputation for invincibility and a number of allies (such equally Byzantium and Naxos in 364 BC) decided to secede.

In 357 BC the revolt confronting the league spread, and between 357 BC and 355 BC, Athens had to face war confronting its allies—a war whose issue was marked by a decisive intervention by the king of Persia in the form of an ultimatum to Athens, enervating that Athens recognise its allies' independence under threat of Persia'due south sending 200 triremes against Athens. Athens had to renounce the war and go out the confederacy, thereby weakening itself more and more, and signaling the terminate of Athenian hegemony.

Theban hegemony – tentative and with no future [edit]

Boetian art, dating from mid-5th century BC

5th century BC Boeotian confederacy (447–386 BC) [edit]

This was non Thebes' showtime attempt at hegemony. Information technology had been the most of import city of Boeotia and the centre of the previous Boeotian confederacy of 447, resurrected since 386.

The 5th-century confederacy is well known to us from a papyrus constitute at Oxyrhynchus and known as "the Anonyme of Thebes". Thebes headed it and gear up a organisation under which charges were divided upward between the different cities of the confederacy. Citizenship was defined co-ordinate to wealth, and Thebes counted eleven,000 active citizens.

The confederacy was divided up into 11 districts, each providing a federal magistrate called a "boeotarch", a certain number of quango members, 1,000 hoplites and 100 horsemen. From the 5th century BC the alliance could field an infantry forcefulness of 11,000 men, in improver to an elite corps and a light infantry numbering 10,000; just its existent power derived from its cavalry strength of i,100, commanded by a federal magistrate contained of local commanders. It as well had a small fleet that played a part in the Peloponnesian State of war by providing 25 triremes for the Spartans. At the end of the conflict, the armada consisted of 50 triremes and was commanded by a "navarch".

All this constituted a significant enough force that the Spartans were happy to see the Boeotian confederacy dissolved by the rex'due south peace. This dissolution, however, did non last, and in the 370s in that location was nothing to stop the Thebans (who had lost the Cadmea to Sparta in 382 BC) from reforming this confederacy.

Theban reconstruction [edit]

Pelopidas and Epaminondas endowed Thebes with democratic institutions similar to those of Athens, the Thebans revived the title of "Boeotarch" lost in the Persian King's Peace and—with victory at Leuctra and the destruction of Spartan ability—the pair achieved their stated objective of renewing the confederacy. Epaminondas rid the Peloponnesus of pro-Spartan oligarchies, replacing them with pro-Theban democracies, constructed cities, and rebuilt a number of those destroyed by Sparta. He equally supported the reconstruction of the city of Messene cheers to an invasion of Laconia that also immune him to liberate the helots and give them Messene equally a capital letter.

He decided in the finish to plant small confederacies all circular the Peloponnessus, forming an Arcadian confederacy (the King's Peace had destroyed a previous Arcadian confederacy and put Messene under Spartan command).

Confrontation between Athens and Thebes [edit]

The strength of the Boeotian League explains Athens' problems with her allies in the second Athenian League. Epaminondas succeeded in disarming his countrymen to build a fleet of 100 triremes to pressure level cities into leaving the Athenian league and joining a Boeotian maritime league. Epaminondas and Pelopidas also reformed the army of Thebes to introduce new and more constructive means of fighting. Thus, the Theban army was able to carry the day against the coalition of other Greek states at the battle of Leuctra in 371 BC and the battle of Mantinea in 362 BC.

Sparta also remained an important power in the face of Theban forcefulness. Yet, some of the cities allied with Sparta turned against her, because of Thebes. In 367 BC, both Sparta and Athens sent delegates to Artaxerxes 2, the Swell Rex of Persia. These delegates sought to have the Artaxerxes, once again, declare Greek independence and a unilateral common peace, just as he had done in twenty years earlier in 387 BC. As noted in a higher place, this had meant the destruction of the Boeotian League in 387 BC. Sparta and Athens now hoped the same affair would happen with a new declaration of a like "Kings Peace". Thebes sent Pelopidas to argue confronting them.[55] The Bully King was convinced by Pelopidas and the Theban diplomats that Thebes and the Boeotian League would be the best agents of Persian interests in Greece, and, accordingly, did not effect a new "Male monarch'south Peace."[48] Thus, to deal with Thebes, Athens and Sparta were thrown back on their own resources. Thebes, meanwhile, expanded its influence beyond the bounds of Boeotia. In 364 BC, Pelopidas defeated the Alexander of Pherae in the Battle of Cynoscephalae, located in south-eastern Thessaly in northern Greece. Still, during the battle, Pelopides was killed.[56]

The confederational framework of Sparta's relationship with her allies was really an artificial one, since it attempted to join cities that had never been able to agree on much at all in the by. Such was the case with the cities of Tegea and Mantinea, which re-allied in the Idealized confederacy. The Mantineans received the back up of the Athenians, and the Tegeans that of the Thebans. In 362 BC, Epaminondas led a Theban army against a coalition of Athenian, Spartan, Elisian, Mantinean and Achean forces. Boxing was joined at Mantinea.[48] The Thebans prevailed, simply this triumph was short-lived, for Epaminondas died in the battle, stating that "I bequeath to Thebes ii daughters, the victory of Leuctra and the victory at Mantinea".

Despite the victory at Mantinea, in the end, the Thebans abased their policy of intervention in the Peloponnesus. This event is looked upon as a watershed in Greek history. Thus, Xenophon concludes his history of the Greek world at this point, in 362 BC. The stop of this menstruation was even more confused than its get-go. Greece had failed and, according to Xenophon, the history of the Greek world was no longer intelligible.

The idea of hegemony disappeared. From 362 BC onward, there was no longer a single urban center that could exert hegemonic ability in Greece. The Spartans were profoundly weakened; the Athenians were in no status to operate their navy, and afterwards 365 no longer had any allies; Thebes could simply exert an ephemeral dominance, and had the means to defeat Sparta and Athens but not to be a major power in Asia Minor.

Other forces also intervened, such equally the Persian king, who appointed himself arbitrator among the Greek cities, with their tacit agreement. This situation reinforced the conflicts and in that location was a proliferation of civil wars, with the confederal framework a repeated trigger for them. One war led to another, each longer and more encarmine than the final, and the bike could not be broken. Hostilities even took identify during winter for the first time, with the invasion of Laconia in 370 BC.

Rise of Macedon [edit]

A wall mural of a charioteer from the Macedonian regal tombs at Vergina, late 6th century BC

Thebes sought to maintain its position until finally eclipsed by the rising power of Macedon in 346 BC. The energetic leadership inside Macedon began in 359 BC when Philip of Macedon was made regent for his nephew, Amyntas. Within a short fourth dimension, Philip was acclaimed male monarch as Philip 2 of Macedonia in his own right, with succession of the throne established on his own heirs.[57] During his lifetime, Philip II consolidated his rule over Macedonia. This was done past 359 BC and Philip began to look toward expanding Republic of macedonia'southward influence away.

Nether Philip 2, (359–336 BC), Macedon expanded into the territory of the Paeonians, Thracians, and Illyrians.[58] In 358 BC, Philip centrolineal with Epirus in its campaign against Illyria. In 357 BC, Philip came into direct conflict with Athens when he conquered the Thracian port city of Amphipolis, a city located at the mouth of the Strymon River to the e of Republic of macedonia, and a major Athenian trading port. Acquisition this city immune Philip to subjugate all of Thrace. A year after in 356 BC, the Macedonians attacked and conquered the Athenian-controlled port city of Pydna. This brought the Macedonian threat to Athens closer to home to the Athenians. With the start of the Phocian State of war in 356 BC, the great Athenian orator and political leader of the "war party", Demosthenes, became increasingly active in encouraging Athens to fight vigorously against Philip's expansionist aims.[59] In 352 BC, Demosthenes gave many speeches against the Macedonian threat, declaring Philip 2 Athens' greatest enemy. The leader of the Athenian "peace party" was Phocion, who wished to avert a confrontation that, Phocion felt, would be catastrophic for Athens. Despite Phocion's attempts to restrain the war party, Athens remained at war with Macedonia for years following the original declaration of war.[sixty] Negotiations between Athens and Philip II started just in 346 BC.[61] The Athenians successfully halted Philip's invasion of Attica at Thermopylae that aforementioned year in 352 BC. All the same, Philip defeated the Phocians at the Battle of the Crocus Field. The disharmonize between Macedonia and all the city-states of Greece came to a caput in 338 BC,[62] at the Battle of Chaeronea.

The Macedonians became more politically involved with the s-primal city-states of Greece, just also retained more than archaic aspects harking dorsum to the palace civilization, first at Aegae (modern Vergina) then at Pella, resembling Mycenaean culture more than that of the Classical city-states. Militarily, Philip recognized the new phalanx style of fighting that had been employed by Epaminondas and Pelopidas in Thebes. Accordingly, he incorporated this new organisation into the Macedonian army. Philip Ii besides brought a Theban armed services tutor to Macedon to instruct the future Alexander the Great in the Theban method of fighting.[63]

Philip's son Alexander the Neat was born in Pella, Republic of macedonia (356–323 BC). Philip Two brought Aristotle to Pella to teach the young Alexander.[64] Besides Alexander'due south female parent, Olympias, Philip took another wife by the name of Cleopatra Eurydice.[65] Cleopatra had a daughter, Europa, and a son, Caranus. Caranus posed a threat to the succession of Alexander.[66] Cleopatra Eurydice was a Macedonian and, thus, Caranus was all Macedonian in blood. Olympias, on the other hand, was from Epirus and, thus, Alexander was regarded as existence only one-half-Macedonian (Cleopatra Eurydice should non be confused with Cleopatra of Macedon, who was Alexander'south full-sis and thus daughter of Philip and Olympias).

Philip II was assassinated at the wedding of his daughter Cleopatra of Macedon with King Alexander I of Epirus in 336 BC.[67] Philip's son, the futurity Alexander the Great, immediately claimed the throne of Republic of macedonia past eliminating all the other claimants to the throne, including Caranus and his cousin Amytas.[68] Alexander was only twenty years of historic period when he causeless the throne.[69]

Thereafter, Alexander connected his male parent's plans to conquer all of Greece. He did this by both military might and persuasion. Afterwards his victory over Thebes, Alexander traveled to Athens to meet the public straight. Despite Demosthenes' speeches against the Macedonian threat on behalf of the state of war party of Athens, the public in Athens was still very much divided between the "peace political party" and Demosthenes' "war party." Withal, the arrival of Alexander charmed the Athenian public.[70] The peace political party was strengthened and so a peace between Athens and Macedonia was agreed.[71] This allowed Alexander to move on his and the Greeks' long-held dream of conquest in the east, with a unified and secure Greek land at his dorsum.

In 334 BC, Alexander with about thirty,000 infantry soldiers and 5,000 cavalry crossed the Hellespont into Asia. He never returned.[72] Alexander managed to briefly extend Macedonian power not only over the central Greek city-states, but also to the Persian empire, including Egypt and lands every bit far east as the fringes of India.[58] He managed to spread Greek culture throughout the known world.[73] Alexander the Groovy died in 323 BC in Babylon during his Asian campaign of conquest.[74]

The Classical catamenia conventionally ends at the expiry of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the fragmentation of his empire, divided amongst the Diadochi,[75] which, in the minds of nearly scholars, marks the beginning of the Hellenistic period.

Legacy of Classical Greece [edit]

The legacy of Greece was strongly felt past mail service-Renaissance European elite, who saw themselves every bit the spiritual heirs of Greece. Will Durant wrote in 1939 that "excepting mechanism, there is hardly anything secular in our culture that does not come up from Hellenic republic," and conversely "there is null in Greek civilisation that doesn't illuminate our own".[76]

Come across also [edit]

- Classical antiquity

- Classics

- Art in ancient Hellenic republic

Notes [edit]

- ^ These sources include Xenophon's continuation of Thucydides' work in his Hellenica, which provided a continuous narrative of Greek history up to 362 BC just has defects, such as bias towards Sparta, with whose king Agesilas Xenophon lived for a while. We likewise accept Plutarch, a 2nd-century Boeotian, whose Life of Pelopidas gives a Theban version of events and Diodorus Siculus. This is also the era where the epigraphic evidence develops, a source of the highest importance for this period, both for Athens and for a number of continental Greek cities that also issued decrees.

References [edit]

- ^ The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the flow from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Nifty in 323 B.C." (Thomas R. Martin, Ancient Greece, Yale University Printing, 1996, p. 94).

- ^ a b Brian Todd Carey, Joshua Allfree, John Cairns. Warfare in the Ancient World Pen and Sword, 19 January 2006 ISBN 1848846304

- ^ a b Aeschylus; Peter Burian; Alan Shapiro (17 February 2009). The Complete Aeschylus: Volume Two: Persians and Other Plays. Oxford University Press. p. xviii. ISBN978-0-19-045183-vii.

- ^ isegoria: equal freedom of speech

- ^ Joseph Roisman,Ian Worthington. "A companion to Ancient Republic of macedonia" John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 144435163X pp. 135–138

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian State of war (Cornell University Printing: Ithaca, New York, 1969) p. 9.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, p. 31.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The Globe of Ancient Times (Charles Scribner's Sons: New York, 1966) pp. 244–248.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 249.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The Earth of Ancient Times, p. 254.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The Earth of Ancient Times, p. 256.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 255.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, p. 10.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, p. 128.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The Globe of Ancient Times, p. 261.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, pp. 2–iii.

- ^ Plutarch, The Age of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives (Penguin Books: New York, 1980) p. 25.

- ^ a b c Plutarch, The Age of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives, p. 26.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian State of war, pp. 206–216.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 278.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, p. 278.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian State of war, pp.252.

- ^ a b c Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times (Charles Scribner's Sons: New York, 1966) p. 287.

- ^ a b c Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition Cornell University Press: New York, 1981) p. 148.

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War: Book 5 (Penguin Books: New York, 1980) pp. 400–408.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Aboriginal Times p. 288.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p. 171.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicialian Expedition, p. 169.

- ^ Donald Kagan,The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The globe of Ancient Times, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Trek, pp. 207–209.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 289.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire (Cornell University Press: New York, 1987) p. 385.

- ^ a b c Plutarch, The Historic period of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives, p. 27.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Aboriginal Times, p. 305.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Plutarch, The Historic period of Alexander, p. 28.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times (Charles Scribner's Sons: New York, 1966) p. 305.

- ^ a b Carl Roebuck, The Earth of Ancient Times, p. 306.

- ^ Plutarch, The Age of Alexander: Ix Greek Lives, pp. 33–38.

- ^ Plutarch, The Age of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives, p. 39.

- ^ Plutarch, The Age of Alexander: 9 Greek Lives, p. 45.

- ^ a b Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 307.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, pp. 307–308.

- ^ a b c Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 308.

- ^ a b c Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 311.

- ^ Plutarch, The Age of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives, p. 81.

- ^ a b Plutarch, The Age of Alexander: 9 Greek Lives, p. 82.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Plutarch, The Age of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives, p. 83.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 309.

- ^ a b c Carl Roebuck, The World of Aboriginal Times, p. 310.

- ^ Plutarch, The Age of Alexander: Ix Greek Lives, p. 97.

- ^ Plutarch, The Historic period of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives, p. 99.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times (Charles Scribner's Sons: New York, 1966) p. 317.

- ^ a b Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 317.

- ^ Plutarch, The Historic period of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives, p. 198.

- ^ Plutarch, The Historic period of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives, p. 231.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The Earth of Aboriginal Times, p. 319.

- ^ Harold Lamb, Alexander of Macedon, p. 65.

- ^ Harold Lamb, Alexander of Macedon (Pinnacle Books: New York, 1946) p. 9.

- ^ Harold Lamb, Alexander of Macedon, p. 30.

- ^ Harold Lamb, Alexander of Macedon, p. 55.

- ^ Harold Lamb, Alexander of Macedon, p. 83.

- ^ Harold Lamb, Alexander of Macedon, p. 82.

- ^ Harold Lamb, Alexander of Macedon, p. 86.

- ^ Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander (Penguin books: New York, 1979) pp. 41–42.

- ^ Harold Lamb, Alexander of Macedon, p. 96.

- ^ Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander, p. 64.

- ^ Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander, p. 65.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The Earth of Ancient Times, p. 349.

- ^ Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander, p. 395.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Aboriginal Times, p. 362.

- ^ Volition Durant, The Life of Hellenic republic (The Story of Civilization, Part II) (New York: Simon & Schuster) 1939: Introduction, pp. seven and eight.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_Greece

0 Response to "based on this map what was true of the two city states that came to dominate ancient greece"

Postar um comentário